Business Professional’s Introduction To Understanding the Blockchain Regulatory Landscape

For enterprises and other businesses looking to leverage distributed ledger technology for competitive advantage, the regulatory uncertainty surrounding blockchain and cryptocurrency has turned hope of compliance into a moving target. By the time you’re done reading our multi-part series, you’ll be smarter than the average lobbyist.

By william.van.winkle

Published:January 4, 2023

19 min read

Many enterprises are considering blockchain technology as an application platform to drive elements of their digital transformation and organizational reinvention. However, the digital ledger waters have been choppy lately. When it comes to the potential adoption of a relatively new but promising business technology such as blockchain, very few market conditions will give pause to organizational executives the way regulatory uncertainty will. At the time that Blockchain Journal published this two-part (see part 2 here) business professional’s guide to understanding the blockchain regulatory landscape, very little certainty has been gained with respect to blockchain and cryptocurrency regulations since Bitcoin first arrived on the scene in 2009. Over the long term, though, weathering the storm will likely prove worthwhile.

Blockchain offers many potential positive outcomes, including competitive advantage, cost management, multi-party transparency, and proof of ESG policy compliance. Because of these incentives, many organizations remain undeterred in their plans. But early adopters and those seeking to gain a business edge would be wise to stay atop the shifting currents of national and international cryptocurrency regulation. In this new world of opportunity, failure to understand regulation can make the difference between successful navigation and untimely misfortune.

How Was the Wild West Won?

As we write this introduction, the US (and possibly global) crypto market appears to be in full meltdown. In May 2022, the implosion of Terra and its LUNA token erased tens of billions of dollars in value. A month later, lending platforms Celsius and Voyager Digital collapsed. A precious few months of peace ensued, only to see leading exchange FTX detonate alongside its sister, Alameda Research. The number of individuals and institutions with significant exposure to FTX’s nuclear fallout is well into the thousands. The contagion’s spread and severity remain to be seen, but calls for regulation now echo throughout the press and across Washington, D.C. as well as governments abroad.

Almost ironically, some industry players, such as Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong, have all but begged the US government for years to establish regulatory clarity. Regulation proponents feel that a strong, effective regulatory framework for the industry will provide the financial and compliance protection needed for institutions to embrace crypto-assets. Meanwhile, regulatory organizations seem content to discuss, debate, delay, and make do with existing laws, some of which are nearly a century old. Conspiracy theorists conjecture that regulatory ambiguity hampers crypto, and thus ultimately aids continued global dominance of the US dollar, even if that means the US will cede control of this emerging, lucrative industry to other nations as crypto-centric businesses seek out friendlier markets.

In late 2021, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) chair Gary Gensler noted, “Currently, we just don’t have enough investor protection in crypto finance, issuance, trading, or lending. Frankly, at this time, it’s more like the Wild West or the old world of ‘buyer beware’ that existed before the Securities laws were enacted. This asset class is rife with fraud, scams, and abuse in certain applications.”

The Wild West is an apt metaphor. In the absence of strong authority across the American frontier, most towns and individuals were left to fend for themselves, sometimes with disastrous results. Over time, though, the Western United States was “tamed” (at least in the US government’s eyes) largely due to railroad infrastructure. Railroads helped to move supplies quickly and improved communications. Yet, in the early, unregulated railroad days, large rail corporations were infamous for their fraud, greed, collusion, and gouging.

By the 1890s, federal regulation was instrumental in bringing order and broader adoption to American railroads. The railroads embraced this regulation out of self-interest. They understood that without regulation, their budding industry would drive away adoption and ultimately rip itself apart. Lack of regulation in the face of certainty that regulation is coming acts like screeching brakes on market development. Sound familiar?

If Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), blockchain, and crypto are indeed “Wild West” tech, then regulation is the means to predictability, protection, and economic growth that enterprises expect of any new technology. Unfortunately, making sense of today’s regulatory environment can be confusing, especially to business and IT executives unversed in regulation. The landscape looks like a patchwork of scattered concepts, disparate (yet possibly overlapping) government stakeholders, and tenuously bridged financial domains. To conclude our railroad analogy, we may be closer to 1865 levels of regulation clarity than 1895, but work continues. Perhaps FTX and its fallout will be the final impetus needed to crystalize crypto-asset governance. Regulatory clarity will create a safe path for enterprises to tread into this new frontier’s economic promise and functional utility.

This Blockchain Journal article and its related follow-ups will collectively offer an introductory framework for approaching what we will, for convenience’s sake, call the crypto regulatory landscape. Our goal is to provide unbiased context and coherence for this complex issue so you can make better-informed decisions regarding how you and your enterprise can interact with digital assets in the future.

Core Concepts

There are many ways to become knowledgeable about DLT and crypto-assets. For example, those needing a better understanding of “what is crypto?” and the distinctions between various tokens and blockchains might benefit by starting with proof of work vs. proof of stake. Within the topic of regulation, though, we need a different view. If we visualized a bull’s-eye target, then the center would likely be securities and commodities, so that is where this piece will concentrate.

What is regulation?

In this context, regulation refers to “a rule or order issued by an executive authority or regulatory agency of a government and having the force of law” (Merriam-Webster). Inevitably, regulations have multiple purposes, such as:

- Guidance for investors. For instance, if you have two different crypto-assets, and US or international lawmakers have ruled one is a commodity while the other is a security, does one type better address an enterprise’s specific technology and investment goals or mandates?

- Discouraging bad actors. As noted earlier, the absence of authority provides opportunities for those who might jump at an opportunity that lacks rules and repercussions. Given today’s headlines, the likelihood of corporate victimhood is a barrier to adoption that enterprises must manage if they intend to unlock the unique value proposition of blockchain as an opportunity for technological disruption.

- Market stability. The cascading slope of imploding businesses and loss of customer value are always a risk, but that risk elevates without regulation.

- Taxation. Governments need tax revenue to maintain operations, and no one wants to pay taxes. Regulations provide a methodology for not only paying those taxes but also budgeting for them. Similar to using tokens at a game arcade, businesses typically must keep a certain amount of cryptocurrency on hand to transact with a public distributed ledger. This “holding” of crypto may or may not have tax implications. This marks an emerging landscape that organizational CFOs will need to keep tabs on.

Regulation aims to bring stability. It sets expectations, establishes a chain of responsibilities and consequences for non-compliance, and makes market functionality more predictable. Ideally, regulation should improve transparency within an industry, although this is obviously sometimes not the case. Interestingly, public distributed ledger technologies stand to make huge strides in advancing transparency. As a proof point, examine the many arrests and asset recaptures enabled by the Bitcoin network’s open, globally distributed ledger system. Every transaction is traceable and open for anyone to examine.

Regulation can also provide investor protection. Existing financial regulations go to considerable lengths to prevent money laundering. As defined by the US government, money laundering “involves disguising financial assets so they can be used without detection of the illegal activity that produced them.” Money laundering often fuels illegal activities and organizations. On a large scale, it also undermines the integrity of a country’s financial infrastructure.

AML and KYC

To counter money-laundering schemes, modern financial regulations typically require a range of anti-money laundering (AML) measures, including due diligence, risk assessment, and monitoring. The US has gradually added successive layers of AML regulation since the 1970’s Bank Secrecy Act, which mandated various measures for record-keeping and transaction reporting. Essentially, AML establishes a trail for authorities to follow back to a source of financial wrongdoing.

AML is often discussed alongside Know Your Customer (KYC) standards. KYC is essentially a subset of AML, and revolves around due diligence and customer identification. When you apply for a new account with a banking or investment service, all that paperwork you fill out to disclose your financial history and identity is part of KYC regulations mandated by the SEC.

Note that AML can preserve user anonymity, or at least pseudonymity, but KYC makes it very hard to do so. Privacy advocates that support peer-to-peer exchange systems (like Bitcoin or Monero) typically take a dim view of regulation-bound fiat and cryptocurrency exchanges, which almost invariably adhere to KYC standards. In contrast, most exchanges welcome AML/KYC measures and are happy to forego anonymity in favor of regulatory compliance.

Regulation vs. enforcement

Laws are designed, debated, and implemented at the national or state level to govern that region’s members equally. In the US, federal bills must pass both the Senate and House of Representatives before being signed into law by the president. Regulations resemble laws, but they are codifications of the specific rules put into place by government departments and agencies in order to implement the associated laws. Regulations provide an agency's interpretation of the law and a documented framework of that interpretation. After understanding that interpretation, which can be thought of as guidance, those who must comply with the law will know what compliance should look like. Similarly, the agency will know what out-of-compliance behavior looks like for the purposes of enforcement. Regulations mandate compliance from pertinent entities such as enterprises, which is why it behooves all businesses to pay close attention to the emerging global cryptocurrency regulation landscape. When an entity fails to comply with regulations, penalties can ensue. Enforcement pertains to the establishment and execution of those penalties.

To illustrate, the SEC creates regulations governing the financial industry, such as KYC and AML mandates. However, within the SEC there is the Division of Enforcement, which investigates potential securities law violations and prosecutes offenders through the country’s courts. Note that enforcement doesn’t inherently mean handcuffs and court dates. US enforcement organizations (the SEC isn’t the only one) often begin with “friendly” advice and persuasion. If that fails, they may present evidence of wrongdoing and seek to enforce compliance through deterrence and threat of penalty. An enforcement organization might seek to make a harsh example of one particularly notable wrongdoer to establish a precedent and set expectations within an industry. Alternatively, not all enforcement is adversarial. Some enforcement groups may work to empower organizations with the tools necessary for more effective self-regulation.

Distinguishing between regulation and enforcement can be challenging, especially within the same agency. The SEC has been grappling with this issue within the context of internet-based securities fraud for decades. As SEC Division of Enforcement Director Richard H. Walker said in 2000, “My preference is to address misconduct in the marketplace through the enforcement process, except when controlling case law prevents us from doing so or conflicting case law creates unreasonable uncertainty. But it may surprise you to hear that I do not believe enforcement authority should be unfettered. True, a metal badge would be nice, but I’m not looking for a gun.”

Enterprises tend to be very leery of new spaces (such as “crypto”) wherein enforcement might precede regulation, and many would choose to wait for regulation rather than risk enforcement. No wonder Fidelity’s October 2022 “Institutional Investor Digital Assets Study” found that 33% of those surveyed had “concerns around the regulatory classification of certain coins as unregistered securities” to be “the greatest overall barrier to investment.” A similar (yet smaller) study by Institutional Investor in November 2022 found that while 71% agree that “crypto valuations will increase over the long term … nearly two-thirds (64%) of crypto intenders cited the need for regulatory clarity as a top consideration in their investment process.”

Various Crypto Instruments

Fidelity’s comment raises an important point: Not all crypto instruments are created equal. (For that matter, not all DLTs are crypto instruments or even blockchain solutions.) Bitcoin “maximalists” are ardent in trumpeting their “Bitcoin, not crypto” distinction, meaning that Bitcoin possesses a set of characteristics that differentiate it from most if not all other crypto offerings. Unpacking this statement alone could fill an entire article, but most of that discussion falls outside the scope of this article’s focus on regulation. Instead, let’s highlight several crypto instrument terms and types.

- Coins and altcoins. Coins function as a transferable unit of value and are based on their underlying native blockchain. For example, Bitcoins (BTC) are native to the Bitcoin blockchain, and Ether (ETH) coins are native to Ethereum. Coins can function as payment or currency tokens (see below) as well as gas/fuel tokens to help service a given distributed ledger's ongoing operation. As Bitcoin was the original blockchain, all coins for subsequent distributed ledgers are called altcoins, although Ethereum's Ether is often considered to be an exception, likely because of its relatively broad adoption.

- Tokens. Tokens represent an asset or utility pertinent to a non-native blockchain. For example, Tether USD (USDT), Shiba Inu (SHIB), and Maker (MKR) are all tokens based on the Ethereum blockchain. There are four primary token types:

- Governance. Governance tokens convey ownership and/or voting rights in an (often decentralized) organization or protocol. To illustrate, the MKR governance token bestows voting rights within the MakerDAO decentralized organization and the Maker Protocol software platform. The decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) and protocol, in turn, manage the issuance and maintenance of the DAI stablecoin.

- Utility. Utility tokens grant holders certain rights to perform actions or claim benefits within a given ecosystem. For example, Filecoin (FIL) is a utility token that gives holders the ability to use the Filecoin decentralized storage platform. With some utility chains, some or all of the utility tokens may be pre-minted, meaning the issuing organization creates the token supply in advance of issuance. Premining can be used for good (incentivizing adoption) or ill (rug-pulling investors) and thus draws considerable regulatory scrutiny. However, true utility tokens may not constitute an investment contract and therefore may fail the all-important Howey test (see below). Without clarity from the SEC on utility tokens or even a reasonable amount of case law precedents, it’s uncertain how utility tokens are classified.

- Payment/currency. Fiat currencies such as the US dollar or the British pound are examples of payment tokens whose initial intent was the widespread acceptance as tender for all goods and services within certain geographic jurisdictions; the territories of the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively. However, given the borderless nature of public DLTs, the word "jurisdiction" has essentially given way to "ecosystem" when it comes to cryptocurrencies. Such ecosystems can be as international and far-reaching as Bitcoin or as small as a specific retailer. In this context, a payment token (sometimes referred to as a "coin"; see above bullet point on coins/alt-coins) broadly represents a transferable store of value that's accepted throughout an ecosystem (and sometimes beyond) as tender for goods and/or services. Payment tokens can also prevent theft and improve security while also strengthening the incentive for users to keep their value within that specific ecosystem. Bitcoin, Ethereum's Ether, and asset-backed stablecoins such as USDT and USD Coin (USDC) are examples of tokens that are widely-used as payment tokens.

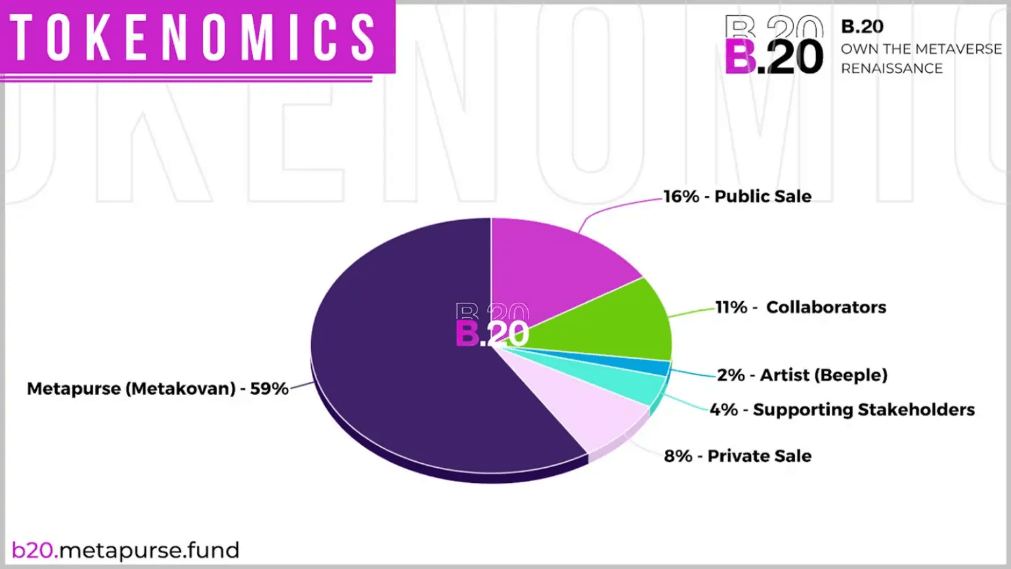

- Security. Security tokens convey partialized ownership in an underlying security asset. The B.20 security token offers one (in)famous example. Investor/speculator Vignesh Sundaresan (aka Metakovan) purchased a Beeple NFT art collection for $2.2 million, bundled it with some metaverse real estate, and tokenized the lot with an Ethereum-based security token issuance called B.20. When B.20 launched in early 2021, each token cost US$2. Within a month, the price peaked at US$23.62. As of this writing, it trades at 11 cents. More importantly, the top 100 B.20 holders own over 87% of the total 10 million-token supply. Only 16% of the supply was ever supposed to reach the public, with the remaining supply shared among project insiders (such as collaborators, artists, and stakeholders). It would be very hard for such a construct not to pass the Howey test.

Despite this lurid example, security tokenization (when properly regulated) may yet provide a flexible, value-rich alternative to conventional stock or asset ownership.

Securities and the SEC

We’ve mentioned “securities” many times in this article without giving a solid explanation of what a security is and why it matters to crypto regulation. Let’s remedy that.

A security is a monetary instrument that holds monetary value and can be traded for money or other goods in a financial market. Often, one hears of equity securities, such as corporate stock. These convey a share of ownership in an enterprise; owners stand to profit through capital gains and regular dividend payments. Conversely, there are also debt securities (such as bonds), wherein owners receive back their invested capital after a given period plus regular interest payments. Hybrid securities can blend these two models, such as when an issued bond converts to stock shares at a specified time. Derivative securities, such as options and futures, are contracts between parties in which the derivative’s value derives from the price of one or more underlying assets (e.g., a house, movie rights to a novel, platinum, pork bellies, sovereign debt risk, etc.).

Securities regulation in the United States generally traces to the Securities Act of 1933, which rose from the wreckage of the 1929 Wall Street Crash and the ensuing Great Depression. The core purpose of the Securities Act was “to provide full and fair disclosure of the character of securities sold in interstate and foreign commerce and through the mails, and to prevent frauds in the sale thereof, and for other purposes.” In other words: mandate honest representation of securities to prospective buyers and eliminate fraud.

The Securities Act established regulations. Enforcement of those regulations quickly passed to the SEC, which was created pursuant to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Consequently, all securities sold in the US must be registered with the SEC.

It didn’t take long for authorities to figure out that regulating the companies that trade securities was just as important as regulating the actual securities. Thus, the Investment Company Act of 1940 was born, which requires that investment companies divulge their activities and financial positions. With this information, investors should be better equipped to know the risks involved in owning securities.

Combined, these early pieces of legislation form the backbone of modern securities regulation. Their antiquated language sometimes references things such as mail and telephone, from which one might infer that the regulations are inapplicable to modern circumstances. However, even the Securities Act mentions “securities sold in interstate and foreign commerce.” This is very broad terminology that can easily apply to the exchange of crypto-assets over the internet. What matters is the transaction, not the medium over which that transaction flows.

The Howey Test

Almost every conversation about cryptocurrency regulation will eventually arrive at the Howey Test. In the context of regulation, the billion-dollar question (sometimes literally) about any coin or token is whether it passes the Howey Test. Given the emerging state of US cryptocurrency regulation, the answer as of this writing was still officially unsettled for all coins and tokens, and unofficially the answer is typically “it depends.” Not surprisingly, for enterprises that prefer not to wait to adopt DLT and cryptocurrency, there’s a fair amount of discomfort with this uncertainty. Thus, it’s advisable to understand the Howey Test, if only to assist in DLT/crypto strategy planning.

William John Howey was a citrus grower in Florida. He owned large tracts of cropland and wanted to increase his monetization of this asset. So, Howey founded a service company, Howey-in-the-Hills, Inc., which retained ownership of half of the citrus groves. The other half was divided into parcels and sold via real estate contracts to generate cash. Purchasers, most of whom had no experience in agriculture and were merely speculating for profit, were persuaded to lease their parcels back to Howey-in-the-Hills, which would then manage the land, harvest the crops, and share the profits. Howey did not register these offerings as securities with the SEC, and the SEC did not approve. The regulatory body determined that Howey’s contracts and leaseback arrangements were, in fact, unregistered securities, and the case ultimately went before the US Supreme Court.

The fundamental question in the case was whether Howey’s offerings constituted an “investment contract.” In 1946, the Supreme Court concluded: “An investment contract for purposes of the Securities Act of 1933 means a contract, transaction, or scheme whereby a person invests his money in a common enterprise and is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party, it being immaterial whether the shares in the enterprise are evidenced by formal certificates or by nominal interests in the physical assets employed in the enterprise.”

The Supreme Court’s smackdown led to what is commonly called the Howey Test. Expressed most simply, if something is an investment contract, it’s a security. How do you know if it’s an investment contract? You run it through the Howey Test and see if it meets four essential criteria:

- Investment of money

- A common enterprise (this has been open to interpretation)

- Reasonable expectation of profit

- Derived from the efforts of others

How does this apply to crypto-assets? It depends. Let’s run Bitcoin through the Howey Test.

- Is there investment of money? Certainly. Anyone or any organization that makes a Bitcoin purchase has invested money.

- Is there a common enterprise? Under one interpretation, probably not. Bitcoin’s creator, pseudonymously known as Satoshi Nakamoto, disappeared shortly after the blockchain’s creation. Bitcoin has no centralized headquarters or governing group. Bitcoin issuance is effectively randomized across miners around the world, and there was never a pre-mine to raise funds from early private investors. On this point, Bitcoin appears to fail the Howey Test.

- Is there a reasonable expectation of profit? Probably. At least, most buyers expect to profit over the long term, although there may be other motivations involved in buying, holding, and transacting in BTC.

- Is this profit derived from the efforts of others? This one is a little fuzzy from a literal, functional perspective. SEC officials have previously said that the answer is “no,” but public statements are not regulations. Whether those opinions eventually end up as laws or regulations remains to be seen.

In contrast, examine the SEC’s December 2020 (and still ongoing) lawsuit against Ripple Labs and its major holders. The SEC alleged that Ripple, beginning in 2013, raised over US$1 billion through the sale of its XRP coin. The suit claims that Ripple’s controlling executives “failed to register their ongoing offer and sale of billions of XRP to retail investors, which deprived potential purchasers of adequate disclosures about XRP and Ripple's business and other important long-standing protections that are fundamental to our robust public market system.” Given the SEC’s pursuit of Ripple in the courts, the agency clearly believes the XRP token constitutes an investment contract. Ripple denies this, saying there is no formal contract between the company and XRP buyers. It’s an example of a confrontation between regulators and the blockchain industry that, including appeals, could take years to resolve. Short of actual laws or regulations that are specific to cryptocurrency, this confrontation showcases the legal uncertainty enterprises face as they guess at what “compliance” looks like while implementing their blockchain strategies.

The Ripple case echoes the SEC’s general stance on initial coin offerings (ICOs). In 2018, then-SEC chairman John Clayton commented to CNBC, “A token, a digital asset, where I give you my money and you go off and make a venture, and in return for giving you my money I say ‘you can get a return’ that is a security and we regulate that.” Clayton also remarked during a 2018 Senate hearing that “I believe every ICO I’ve seen is a security.”

The Howey Test and defining a security are critical to organizations making strategic investments into blockchain as an application platform or cryptocurrency itself (e.g., something as simple as paying employees in Bitcoin). A smaller company might wish to tokenize a portion of company ownership to raise funds rather than go through an IPO. A company might tokenize some of its tangible assets or even its intellectual property. It might want to institute a service that’s redeemable with company-specific tokens or even convert itself into a DAO, complete with a governance token issuance for stakeholders. Which of these are securities? Which, if any, are only utility tokens and not subject to SEC regulation? We must distinguish between Howey’s orange groves and the instruments used for capitalizing on them.

In this article, we took a long look into the foundations of securities and their regulation, but this is only the beginning. In the second part of Blockchain Journal's two-part business professional’s guide to blockchain regulation, we’ll turn to commodities and currencies, both of which operate very differently from securities. Together, these two resources will offer a strong overview of today’s regulatory space and how enterprises can consider their emerging DLT and crypto involvement within that regulatory context.