How an NFL Team (and its Fans) Could Have Benefitted from the Inherent Multi-Party Transparency of Public Blockchain

According to multiple lawsuits, the Washington Commanders, an NFL franchise, has allegedly misappropriated the financial deposits of its fans. Could blockchain’s multi-party transparency and auditability have simultaneously protected the interests of fans as well as the team, and even the NFL?

Published:January 4, 2023

10 min read

- One of the benefits of public distributed ledgers has to do with how the data that’s published to them is available for any stakeholder with internet access to see. There are many business use cases to which this sort of inherent automatic multi-party transparency introduces a desirable element of risk management that other technologies do not

- The Washington Commanders, a Washington, DC-based football team that’s a part of the National Football League (NFL), is being sued by both its fans and the local Attorney General for its alleged failure to return security deposits belonging to those fans

- The situation begs the question of whether the expenditure of legal resources, the degree to which the team’s and the league’s brands have been sullied, and the emotional and financial distress caused to fans could all have been averted with the help of public distributed ledger technology (DLT) and smart contracts

- As with other use cases for public DLT, whereas some data is, “on-chain” and available to see, other data such as personally identifiable information can be kept “off-chain”

These days, most people tend to think of blockchain technology as the foundational mechanism for storing and transferring cryptocurrencies. This makes sense given that the relationship between cryptocurrency and blockchain is where the mainstream media typically focuses its attention. However, blockchain has other features that go beyond supporting the cryptocurrency ecosystem. One of those features is transparency, and it’s important.

Transparency, which is inherent in any public distributed ledger, enables anybody to look at any aspect of the given blockchain at any time. This is a big deal because a distributed ledger’s inborn transparency makes a public blockchain universally auditable by anyone; an individual, an organization, or a government agency. Anybody can audit a public blockchain by jumping on the internet and using any one of the many freely available Digital Ledger Technology (DLT) inspection tools (aka blockchain explorers).

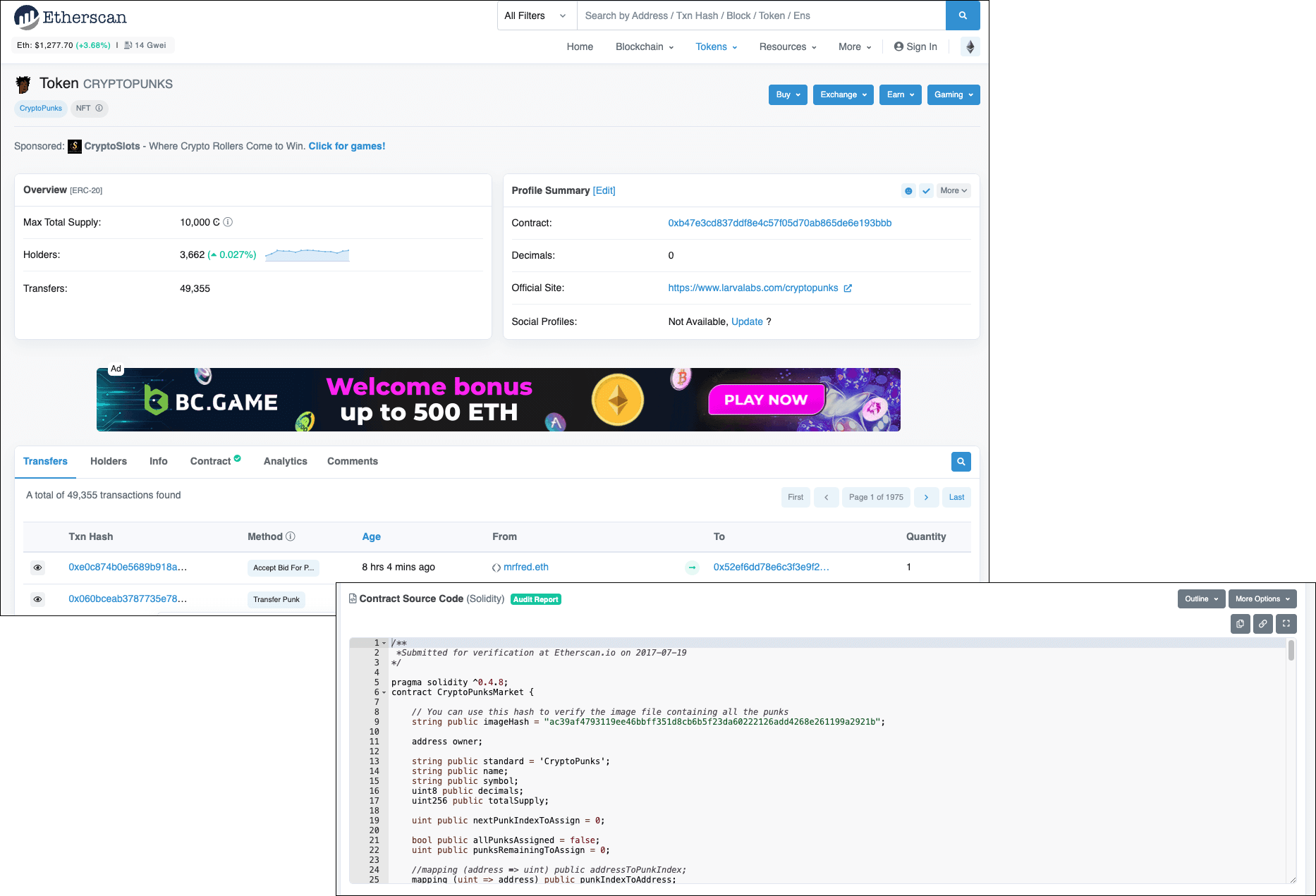

Figure 1: All data, including smart contract code, is auditable on a public blockchain by anyone. (Using Etherscan.io to view a transaction)

The thing to understand about universal auditability is that it goes way beyond the notion of public access. Public access means that an organization can grant access to all or a portion of its network to the public. That network, and the hardware on which the network runs, is private to the given organization. The organization can decide whether to make a portion or even all of its network accessible to the public. It’s a great value add, maybe even essential as a public service. But, that access can be revoked at any moment without notice.

On the other hand, as long as a public blockchain is sufficiently decentralized to the point that no single party or group of colluding parties can assert its control over the healthy operation of that chain, public access to it is irrevocable. Its data, immutably recorded for as long as the chain’s decentralized community is willing to support it, is always available for audit.

Blockchain’s Universal Auditability

Blockchain is universally auditable because the networks on which public blockchains run are not owned or controlled by a single organization, such as a bank that has total control over its systems. Rather, blockchains typically involve many computers (called nodes) operating in peer-to-peer fashion, which results in each computer having identical copies of the network’s data. That data is continuously replicated to each node using broadcast, security, and data management protocols that are supported by every node on the network. With blockchain – and in particular, the public distributed ledger type of blockchain – there is no access to be granted because there is no central authority to manage that access. The network is the authority and the protocols are the rules by which all nodes abide. As a result, similar to the internet which also operates according to standard protocols, the network is open and always accessible.

However, universal access is not a free-for-all. The open nature of the blockchain doesn’t mean that anybody can add data to the public distributed ledger at any time. The ledger’s protocols make it so that new data has to go through a stringent, protocol-driven, validation process before it can be added to the network. Once added though, blockchain protocols prevent modifications to existing data on the network; a DLT feature known as “immutability.”

This isn’t to say that blockchain and open networks should be the end goal of enterprise architectures everywhere. Quite the contrary. Private technology installations provide benefits. For example, the possibility of anyone looking at pre-release versions of the next Star Wars movie is probably one of Disney’s worst security nightmares. Rightfully so, protecting the secrecy of confidential intellectual property is an essential aspect of any business operation, which is why there are some use cases to which a public blockchain simply doesn’t apply.

However, while there are plenty of use cases that may not be a great fit for DLT, there are also many scenarios where it makes sense for data to be publicly available and universally auditable. Also, you want to ensure that public access is available by default, not by having to grant special access rights. This is where the inherently transparent nature of the blockchain comes into play. Consider the following real-world scenario.

A Case in Point

On Nov 17, 2022 the Attorney General of Washington DC filed a lawsuit against the Washington Commanders Football Team, alleging that:

… the Team prioritized its own revenues over fairness and deceived District consumers by wrongly withholding their security deposits that should have been automatically repaid under consumers’ contracts, and improperly using those deposits for the Team’s own purposes.

The lawsuit further states that,

Although the Team promised those consumers through its 2 contracts that it would automatically return the deposits within 30 days of the contract’s expiration, the Team instead deceptively held onto these funds—sometimes for over a decade—and used the money for its own purposes. The Team capitalized on the fact that at the end of a long-term contract, many consumers simply forgot that they had ever paid a security deposit.

In short, the lawsuit alleges that the team took security deposits from the general public for season tickets to football games and then did not refund the deposits when the ticket contract expired. As mentioned in the lawsuit, the practice went on for a decade. USA Today reports that the team withheld $5 million in refundable deposits. The amount is far from trivial.

So, what does this have to do with blockchain transparency?

For all intents and purposes, the season ticket contract sold by the Washington Commanders and for which the team required a security deposit was a public offering. There was no restriction on who could buy a season ticket. As long as you had the money, you could make the purchase. Again, the offer was open to the public, with special emphasis on the term, public.

However, once that purchase was made, both the money and the record of the purchase became private. The purchaser might’ve received a receipt of the purchase and a copy of the purchase contract for their records, but essentially all the data and the money relevant to the given purchase lived inside the football team’s private network. The information about the season ticket purchase was stored in databases within the private network. The money collected from purchases was deposited in bank accounts that were private to the corporation that owns the football team.

The purchasers may have been able to view information about their season tickets on the football team’s website. But, exactly what information the purchaser could see was decided by the owners of the football team? If there aren’t any laws about public disclosure in place, the owners can decide to not show any information at all. In that case, all the purchaser has is a receipt proving the purchase, the ticket, and maybe the contract. The purchaser has no idea where the money went nor any insight into how the refund process works other than a statement in the contract.

Overall, it doesn’t seem like a big deal. It happens every day. Landlords collect security deposits from prospective tenants; some bowling alleys collect a deposit when they rent you bowling shoes. Where that money goes is anybody’s guess. Nobody really cares… until something bad happens.

What if you’re a renter who is moving to another location and are depending on the security deposit refund for other purposes? Or, what if you’re the purchaser of a season ticket to Washington Commanders football games and plan to use the deposit money to go on vacation after the season is over? What if you forget you made a deposit? Or most importantly, what if the deposit is never refunded, what then?

You can demand your money back, or if you’re fortunate enough, the Attorney General for the District of Columbia sues the team. Then the real action begins.

The case has to go to court. The Attorney General builds a case to prove the money was never refunded. If the judgment favors the Attorney General (and the public), the court forces the football team to pay up. Should the football team drag its feet, auditing and legal back-and-forth will be necessary to get payment expedited. But, what if the team spent all the deposit money and there’s nothing left? Then things get even more complicated. And, at the end of the day, the purchasers–the public–are left holding the bag throughout a lengthy legal process that might go on for years.

But there is a better way.

What If?

What if the whole matter from start to finish was conducted on a public blockchain? What if the ticket, the contract, the record of the ticket purchase, the money used for the ticket purchase, as well as the execution of the contract was part of a public blockchain that could be audited by anybody at any time? Then it’s a whole new ballgame, no pun intended.

This is where the inherent multi-party transparent nature of blockchain comes into play.

The key thing to remember, as mentioned above, is that the sale of season tickets in the Washington Commanders case was a public offering. We’re not talking about the exchange of state secrets. It’s about a commercial, contractual agreement intended for the general public. Thus, there is ample justification for putting all matters relevant to the season ticket offering on a public blockchain.

Once all the information relevant to the season ticket offering is put on the blockchain, everything becomes auditable by anybody at any time. It’s hard to get away with something when everybody is watching. Also, just to be clear, any personally identifiable information–what privacy experts refer to as PII–does not have to be kept in public view. Whereas the transactional data requiring some degree of multi-party transparency is immutably kept in public view using a public DLT (often referred to as data that’s “on-chain”), the PII to which that transaction is linked can be encrypted and kept off-chain in ways that only authorized parties can view it.

More importantly, thanks in part to smart contract technology–which turns distributed ledgers into full-blown application platforms–some of today’s chains can store data and execute programs that collect and refund money without human intervention or interlocution. It’s second nature for a developer to write a program that runs on the blockchain that monitors season ticket activity and then, if all is well, refunds the purchaser’s security deposit automatically at the end of the season, using funds that are stored on the blockchain. Blockchains around the world are executing programs of this type every day.

As shown in Figure 1 above, once you put data on a public blockchain, it’s all auditable. Anybody with an internet connection can inspect all of the aspects of the offering including the code that’s running the application that executes the refunds. Using a public blockchain would indeed make such a public offering really, really public. Also, using a public blockchain can hold the company making the public offering accountable, which not only protects its customers, but it also protects the organization from lawsuits, the brand from being unnecessarily tarnished, employees from being guilty by association, and partner organizations such as the NFL, in this case, from becoming collateral damage. In other words, organizations should not just want this sort of risk management for their customers, they should want it for themselves.

Doing the Right Thing and Proving It

Today, many companies advertise intentions of acting responsibly when it comes to the public good, particularly around green energy. Yet, how can we tell if they actually are? Often, evaluating that companies are doing the right thing is conducted according to the data the companies provide.

For example, when reporting the source of some of its data in its study titled, Corporate Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor 2022, the New Climate Institute states that

“Sony discloses detailed information on emissions in tabular format…” and “Vodafone makes its full dataset for its Environmental, Social and Governance [ESG] reporting available for download in a transparent workbook.”

The fact is the Sony and Vodafone giveth and Sony and Vodafone can taketh away. The data is being shared because these companies want to share the data. What if they don’t? And how many levels of executive sanitizing did the data experience before it finally entered the public domain?

Why not just cut to the chase and put all the data out on a blockchain for anybody to see? As mentioned previously, these are not state secrets. This information is critical to the well-being of the public. We can hope companies are holding themselves accountable for their behavior. But, do we really know for sure? Maybe yes, maybe no. But, particularly in the case of the E in ESG, if an organization’s carbon emissions and carbon offset data were immutably recorded to a public blockchain as those events took place, we would really know for sure.

It all comes down to this: When a company says it’s doing the right thing, it needs to hold itself accountable for its behavior. In other words, it needs to verifiably prove it to its customers, its stockholders, its employees, its partners, and in many cases where compliance is a requirement, to regulators.

One of the easiest ways for a company to prove it's walking its talk–whether it's the Washington Commanders or ExxonMobil – is by providing information that should be public–really and truly public–on a public blockchain and making it transparent to anybody, from anywhere, all the time.