Blockchain Journal’s Database Fuels Discovery of NFT Best Practices by Starbucks, Adidas, RTFKT, Others

While blockchain itself has been around for more than a decade, it is only in the last year that global enterprises have, relatively en masse, started to explore how distributed ledger technologies (DLT) might give them an edge within their various industries. Behind the scenes at Blockchain Journal, we’ve been developing a research database that aims to capture the full extent of these activities, chronicling the myriad projects, their timelines, and their reliance on more than blockchain technology itself to achieve certain business outcomes.

Published: July 24, 2023

6 min read

We’re building this database to serve as both a source of inspiration for Blockchain Journal’s content as well as a source of research for CIOs, IT directors, corporate developers and other business visitors wanting to better understand the blockchain journeys taken by other enterprises. One example of something surprising that was learned as we’ve been building this database is that it's harder to find a car manufacturer that isn’t doing something with DLT than it is to find one that is. Across its Toyota and Lexus brands for example, Toyota has four separate blockchain projects in the works. Across most major industries from Automotive to Fashion/Apparel to Sports to Foodservice, the blockchain train is unquestionably leaving the station.

From our research, something else that’s become very clear – almost painfully so – is that there are no public-facing Customer Blockchain Experiences (CBEs) that are turnkey in nature. Regardless of which program we study, it’s very clear that, given the state of the DLT industry, enterprises have no choice but to stitch multiple technologies together into a patchwork quilt of solutions that, in some cases, may not have been originally meant to be quilted together. As with the beginning of almost all previous digital revolutions, there’s a burden on end users to be system integrators. This burden varies from one CBE to the next and is highly dependent on the work and investment that organizations are willing to commit in order to smooth out the seams as best as they possibly can.

For example, whereas the totality of the long-running Starbucks’ Rewards customer loyalty program is very well self-contained within a nearly frictionless mobile application behind which there are probably 25 or more different technologies at play, the seams between the various technologies used to offer Starbucks’ Odyssey non-fungible token (NFT) program are not nearly as smooth for the company’s customers.

That was in no way a criticism of the Odyssey program. The same can be said of virtually every other program we’ve encountered so far. In fact, in some cases, Starbucks has gone further than others to give its users a better glide path between the different technologies that form its end-to-end CBE. The fact that every CBE involves varying degrees of friction is a reflection of the blockchain industry’s very nascent state, particularly when it comes to satisfying the sophisticated requirements of enterprises that are used to delivering seamless experiences to their many constituencies (customers, employees, partners, suppliers, etc.).

At bare minimum, Blockchain Journal will be using this database as the foundation for two types of content that we’ll be offering to enterprises and businesses. The first of these two types is our Enterprise Blockchain Adoption Tracker (EBAT). Over the last four decades of information technology (IT) – and particularly during tipping points of the sort that blockchain is poised to inspire – most businesses learned from and mimicked the successes and failures of other enterprises that tried to put the point-tipping tech to work.

Under the hood of our EBAT, our custom-built database is not only making a record of each enterprise project’s existence, it is tracking and categorizing the milestones – good or bad – of those projects in a way that will help our readers to visualize what the journey is like once a business undertakes a blockchain initiative. Each adoption tracker we publish offers a bit of color commentary about a single milestone in the form of a snackable post, so that business and technology decision-makers can easily visualize the blockchain journeys of other enterprises in their industries and beyond. As can be seen from these adoption trackers, we are researching and reconstructing the history of the many enterprises whose journeys started in advance of Blockchain Journal’s founding.

The second of the two types of content facilitated by our database are our use case and best practice articles, also designed and written to help our business audiences learn from the success and failures of their peers. As our database helped us to visualize the formation of each project’s patchwork quilt, it wasn’t long before we began to spot significant operational differences from one program to the next.

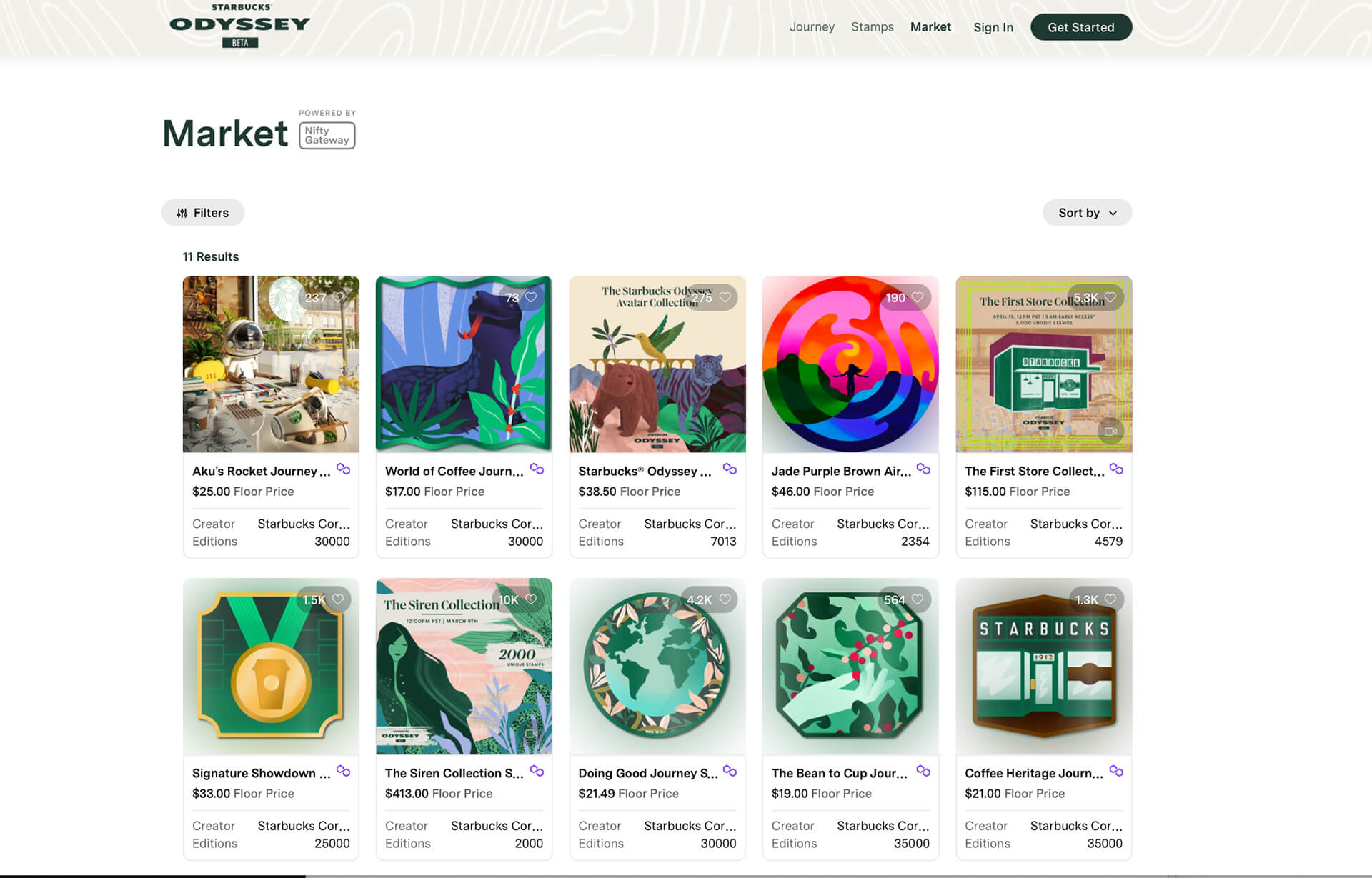

For primary and secondary market NFT sales, Starbucks’ Odyssey NFT program mainly relies on Nifty Gateway’s marketplace technology, which can be privately labeled and supports transactions in US dollars (versus cryptocurrency).

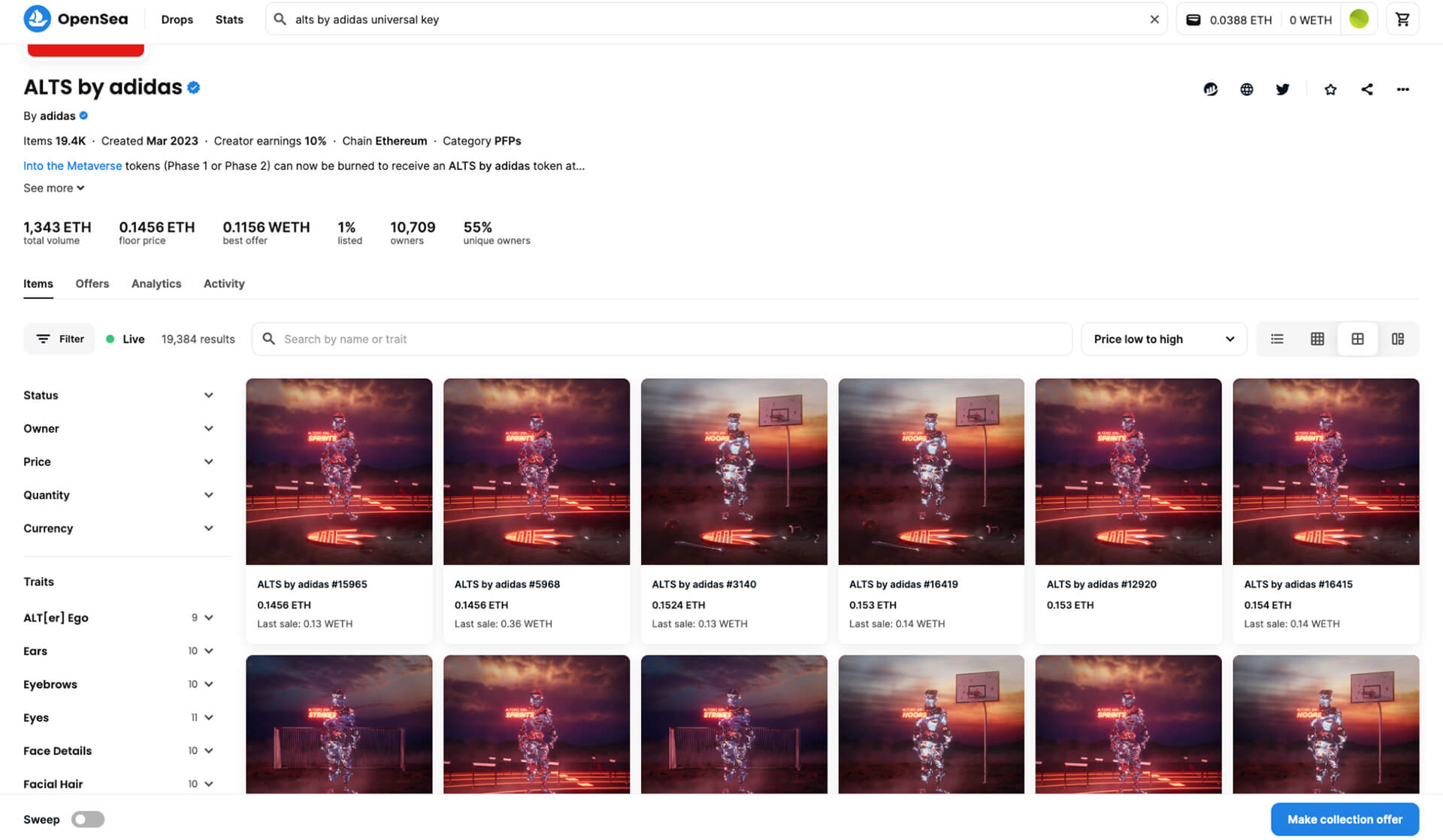

For example, whereas the Starbucks Odyssey program makes use of Nifty Gateway’s privately labeled NFT marketplace, the ALTs by Adidas NFT project primarily relies on OpenSea. For Starbucks and Nifty’s other customers, Nifty Gateway��’s (an offering from Gemini Trust Company, which is associated with the infamous twins Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss) features include a custodial wallet, protection from sales of counterfeit NFTs, and the ability to transact in US dollars (as opposed to cryptocurrency). Starbucks’ reliance on Nifty Gateway is more of a blend of old- and new-world technology (often described as “Web 2.5” in blockchain parlance) versus the decidedly more Web 3.0-esque approach taken by adidas where customers must bring their own cryptocurrency wallets (typically MetaMask), counterfeit NFTs on OpenSea are a risk, and Ether (aka “ETH.” the protocol token of the Ethereum blockchain) is used for NFT sales and purchases.

For its Alts by adidas NFT project (formerly “adidas Originals: Into the Metaverse”), adidas relies on OpenSea marketplace technology for the primary and secondary sales of its NFTs.

There are many nuanced pros and cons to these and the other approaches taken by some enterprises when it comes to facilitating primary and secondary NFT sales within their own patchwork quilts. Blockchain Journal’s database is under the hood, helping us to not only discover these nuances, but to write targeted, prescriptive articles about them in a way that other enterprises can learn from the blockchain project work of their peers. Our best practice article about how the NFT consultancy RTFKT helped luxury luggage manufacturer Rimowa to nail the all-important NFT drop FAQ is the first of what will be many of these narrowly targeted articles. In December 2021, after RTFKT demonstrated a knack for applying NFT technology to sneakers, Nike acquired the company and integrated it into a division – Nike Virtual Studios – that was formed to lead the sports apparel company’s charge into the metaverse. Taken together, we expect these articles in aggregate to form the basis of playbooks for different project types (i.e., NFT & metaverse, supply chain, financial asset tokenization, etc.).

Over time, our plan is to build a variety of automatic and user-customizable views to this database. Whereas the automatic views will consist of special web pages through which Blockchain Journal’s audience can intuitively discover the projects, milestones, and other data by simply clicking around (e.g., starting with an organization name like The California DMV or Fox Entertainment and double-clicking into their projects, milestones, and other pertinent data), user-customization will come in the form of power-search capabilities that enable queries like “Show me all the enterprise NFT projects that use OpenSea, Ethereum, and Discord.”

Before this research database existed, it was hard for us to envision these sorts of birds-eye views that are now taking shape in our minds. Undoubtedly, the more data we collect, the more discoveries that can be made to pivot that data into teachable moments that even we cannot yet imagine.