The Lawmaker and Business Executive's Guide To The Non-Crypto Applications of Blockchain

Whereas the US is typically known for its global leadership on emergent computer technologies, most American companies are sitting on the sidelines as blockchain gains traction in other parts of the world. Business leaders point to three fixable problems: a failure to understand the non-crypto applications of blockchain, a perception that it’s guilty by association with cryptocurrency, and a dearth of regulatory clarity. Blockchain Journal explains.

Published: January 13, 2024

30 min read

In this article:

- New technologies that require little more than a grade-schooler's knowledge of smartphone operation are enabling the fabrication (disinformation) and viral distribution (misinformation) of plausible and convincing alternate realities that undermine the perception of facts and truth.

- Many of the world’s most relied-upon institutions are experiencing a catastrophic erosion in trust; an erosion that is not only a threat to organizational viability, but also to the stability of modern society.

- Much of this erosion is attributable to the negligent — if not fraudulent — governance of institutional business processes and recordkeeping and the failure to protect data from internal and external threats.

- Despite how well-known it is for supporting financial transactions involving cryptocurrency, blockchain technology is uniquely positioned to benefit many other applications across business, government, and other organizational domains. They don’t need to be financial in nature.

- The most important of those use cases involves the programmatic infusion of trust into existing and new applications with an eye toward the restoration of our faith in the institutions on which we depend for truthful professional, governmental, religious and personal interactions.

- From the C-suite to the halls of the US government, it is imperative to disentangle blockchain technology from the legitimate concerns over cryptocurrency. This will help ensure that regulatory uncertainty and business hesitation surrounding crypto do not impede unbridled innovation with blockchain technology (as has traditionally been the case in the US with other emergent digital technologies).

If you, your constituents, friends, colleagues, or family members ever questioned the veracity of an entity’s records (financial or otherwise) or ever wondered why such records didn’t exist when they should have, or felt as though you deserved access to records that for some reason were unavailable to you, then this article about the game-changing significance of blockchain, far above and beyond the sensational trend of cryptocurrency, is for you.

Contrary to common belief, blockchain’s big idea is not about crypto; it’s about trust. More specifically, who do you trust? And at a time when trust is being tested when it comes to the institutions on which every human depends (business, government, not-for-profit, etc.), blockchain technology — completely unrelated to crypto — represents a unique and crucial opportunity to not only revitalize that trust but to infuse trust into a new class of applications that are capable of driving economic growth.

However, even though some American enterprises are aware of blockchain’s game-changing potential, they are loath to begin any innovation so long as blockchain’s regulatory future remains tied to that of cryptocurrency. Lawmakers and regulators need to disentangle their contemplations about the two in a way that offers US businesses some regulatory clarity when it comes to blockchain itself. Once that happens, a new wave of innovation will follow.

The World’s Expanding Reliance on Institutional Recordkeeping

Were it not for the voluminous records kept by the world’s businesses, governments, and other institutions, modern society as we know it could not exist. Voting records. Medical records. Academic records. Phone records. DMV records. Video records. Travel records. Building entry and exit records. And of course, financial records, just to name a few. Imagine the pandemonium if all of it were kept on one computer and that computer crashed. There was a moment in time — December 31, 1999 — when the world braced for this very chaos. Many believed that millions of computers and programs were on the brink of failure as their clocks ticked past midnight into the year 2000.

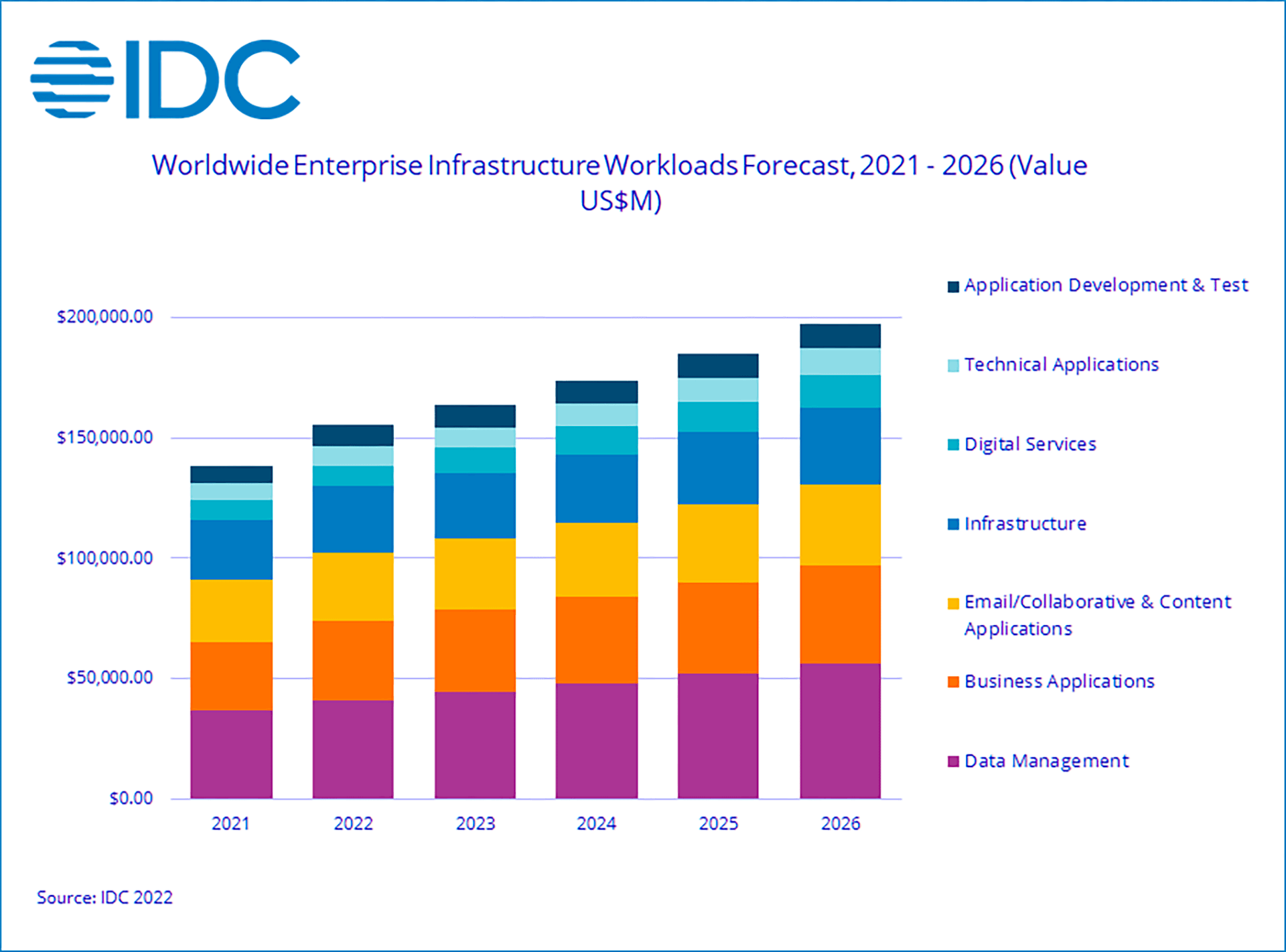

Fortunately, the so-called Y2K problem was a nothing burger, and the human race carried on. But so has its dependence on records. According to IDC, structured data management — the unquestionable foundation of modern recordkeeping — has, and continues to be the largest category of enterprise infrastructure spending. As part of a study published in November 2022, IDC stated the following:

In 2022, the Data Management workload category … will be the largest with $41.1 billion in spending on compute and storage infrastructure products. It will remain the largest throughout the forecast period with a five-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9% and reaching $56.3 billion in infrastructure spending in 2026.

Not surprisingly, the report also cited the barely discussed (at that time) artificial intelligence market, now on the verge of eruption, as being a major driver of this growth going forward.

Dating back to 2021 and looking forward to 2026, IDC research suggests that the Data Management category (shown in purple) is annually repeating as the largest of seven enterprise infrastructure workload categories.

In other words, today’s institutions are exhibiting a nearly insatiable appetite to oversee and profit from the world’s data. Society has grown so dependent on records that some of us unscrupulously fabricate entire digital recordkeeping infrastructures just to portray the convincing illusion of legitimacy. It’s in a computer. It’s on the web. Therefore, it must be true. Even crooks rely on records — truthful ones — to keep track of their felonious activities.

Despite Strong Enforcement, Fraudulent Recordkeeping Continues Unabated

But, as much as those records — the way they’re conceived, stored, retrieved, and presented — have served the greater good of mankind for the last century, we’re on the verge of a new era when the veracity of the world’s data and the integrities of its caretakers are too easily challenged. A quick scan of the press releases published by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reveals a parade of theoretically trustworthy brands that — by way of malicious intent or incompetence — have been fined millions, and in some cases, billions of dollars for fraudulent recordkeeping or negligent business practices; transgressions that a more trustworthy system of data governance and transparency might have prevented.

And those are just the organizations that got caught. Every day, innocent bystanders to these malevolent organizations are adversely affected because of poorly governed business processes and practices. Chief executives and lawmakers should proactively seek technological remedies, legislative frameworks, and other means to resolve these issues as soon as possible.

During a Blockchain Journal interview at the DC Blockchain Summit in 2023, Deloitte’s Principal Leader of Trust Michael Bondar commented:

We see pretty consistent fractures or a decline in trust … In healthcare, for example, only 23% of clinicians trust their leadership. That number goes down to 15% for nurses. In technology, only 40% of consumers trust tech companies to maintain and safeguard their data. So we're talking about a low level of trust across the world. So that decline is consistently seen and will only continue unless companies take proactive action and not wait for a crisis to emerge.

Deloitte is not alone in reaching such sobering conclusions about the state of trust across many of the world’s institutions. After seeing the Battle in Seattle protests against globalization in 1999 in the news, Richard Edelman, CEO of Edelman Public Relations (the largest PR firm in the world) launched the firm’s annual Trust Barometer; a survey to understand why people were so trusting of non-government organizations (NGOs) over other institutions.

The Trust Barometer survey, now in its 24th year, reaches over 32,000 respondents spanning 28 countries and has perennially concluded that trust is not only problematic, but the lack of it represents an opportunity for all kinds of entities — businesses, political parties, and other organizations — to seize competitive advantage. The 2023 edition of the survey found that 38% of the respondents did not trust businesses. Meanwhile, only 50% viewed government and media organizations as being trustworthy.

In an interview with Blockchain Journal, Edelman’s executive director of the Trust Barometer Tonia Ries said:

Trust is shifting. Over time, we have documented power shifts and deepening divisions that require new ways of thinking about trust—who has it, how do you earn and keep it? Forward-thinking organizations should take the view that there now exists a market opportunity to not only engender trust but to use that trust to drive competitive advantage.

Trust in some of the world’s most important records and their stewards is not only evaporating, it is on course to a potentially catastrophic consequence: the acute destabilization of an already fragile geopolitical climate. A fitting example of this is the long-running controversy over the results of the US Presidential election. There are at least two non-partisan features of the conflict at hand.

First, the very essence of that conflict involves a fundamental disagreement over recordkeeping practices. What records were kept? What records were not (and maybe in hindsight should have been)? How were those records kept? Who can view them? Who tampered with them (or didn’t)? How do we know which records are truthful and which are not?

Second, whatever records were kept, we wish the virtue of those records would have led to a more expeditious resolution of the conflict. They didn’t. Where there should be a single source of truth, both sides claim to be operating from separate sets of facts. One side says the books were cooked. The other says they weren’t. A single source of the truth — in the form of significantly improved recordkeeping practices — should be more readily and transparently available to any stakeholder in any process, whether it's government, business, or otherwise.

Where There's Transparency, There's Improved Trust. And Profits.

While Richard Edelman saw trust in today’s institutions as a festering problem deserving of more awareness, Salesforce co-founder, Chairman, and CEO Marc Benioff saw both the virtue and the business opportunity in being one of the most, if not the most trusted business on the planet, and then acted on those instincts.

In the early 2000s, under the moniker of “No Software,” Benioff and Salesforce were capitalizing on the computing public’s waning faith in Microsoft’s operating systems and applications due to a seemingly interminable string of exploits and hacks. Rather than require users to install and run software locally on their desktops and servers as had been traditionally done for two decades, Salesforce — in true software-as-a-service fashion — hosted its application's business logic in its data centers and required nothing more of end-users but a web browser to access its customer relationship management (CRM) technology. However, Salesforce inspired innovation in the form of other cloud companies.

And then, heading into the 2010s, some of those companies were gaining notoriety for some high-profile outages that diluted trust in the overall cloud. Users of Google’s Gmail were regularly victimized by the email service’s outages. Additionally, the list of companies whose websites were inaccessible due to problems with Amazon’s Web Services read like a Who’s Who of Silicon Valley. Not to mention Twitter and its once notorious “Fail Whale.”

Knowing how trust (or lack thereof) could impact the success of his business — and having already seen the Microsoft movie play itself out — Benioff went on a trust campaign that, until this day, unassailably persists as every Salesforce employee’s top priority. But he didn’t stop there. Anticipating that multi-party transparency would be the key to “earning and keeping trust” (as Edelman’s Ries put it), Benioff and team launched trust.salesforce.com in 2006; a dashboard that continues to be the standard-bearer for transparency when it comes to the health of a cloud provider’s systems and data centers.

To get an idea of just how important transparency is to Benioff’s mission of trust, one needs only to read the first method of engendering trust in the dashboard’s tagline: “We earn the trust of our customers, employees, and extended family through transparency, security, compliance, privacy, and performance. And we deliver the industry's most trusted infrastructure.”

Benioff bet the farm — and is winning — based on trust. In 2014, he told Forbes.com “That's the product that we sell, trust. Customers work with us because they trust us, and employees work for us because they trust us."

Since then, Benioff has only doubled down. In 2019, he told The Verge:

Nothing is more important than the trust you have with your customers, employees, partners, shareholders, and all stakeholders. And trust has to be your highest value. People either trust you or they don’t. Every person needs to ask the question: what is our highest value? And if trust isn’t your highest value, then what is it? If your highest value is power and control, or money, or innovation, or anything else, it’s not correct.

In the years since 2006 when the trust.salesforce.com site was first launched, the dashboard has evolved to be so alarmingly transparent (compared to industry norms) when it comes to the internal operational data (health, uptime, performance, etc.) that it makes public, it’s almost as if the company’s system engineers have challenged themselves to discover any bits of data they haven’t disclosed.

Salesforce is a shining example of how multi-party transparency concerning a company’s internal business processes, data, and recordkeeping practices can “earn and keep” trust — and this has inspired many organizations to follow its lead. However, there remains an additional opportunity to not only take that trust to an entirely new level, but to defend against the growing threats of deep fakes, hackers (external or internal), disinformation (and its kissing cousin, misinformation), and artificial intelligence.

Enter Blockchain.

Trust: The Lesser-Known Unique Value Proposition of Blockchain

A small handful of industry observers (some would say “too small”) are quick to note that blockchain technology can be used to infuse trust into a wide range of non-crypto applications. “Blockchain is a trust machine,” Deloitte’s Bondar told Blockchain Journal when asked about why someone with the title Principal Leader of Trust would be attending a blockchain event.

Rosie Gillam, executive vice president of Edelman-Smithfield, echoes this notion:

I expect, as companies employ blockchain technology for new kinds of applications, we will see trust in business continue to climb. For example, when it comes to supply chain management, blockchain technology is giving suppliers the unique ability to trace products as they advance along every stage of the value chain, from manufacturing up through distribution. This level of traceability in the movement of assets is beneficial to businesses and their customers as transparency is a core tenant in building and maintaining trust.

Gillam also noted blockchain’s nascent superpower in dealing with one of today’s most confounding scourges of society:

Another way that blockchain is being employed is to combat disinformation, which is a key eroder of trust. From verifying provenance to authenticating the identity of a content creator, blockchain is being employed in a number of different ways to establish consistent standards for identifying, monitoring and even responding to manipulated media online.

Unfortunately, blockchain’s ability to infuse trust and transparency into business and recordkeeping processes is not widely understood, especially among lawmakers, chief executives, and anybody else whose comprehension of blockchain is overshadowed by its connection to crypto. As if to exacerbate this lack of understanding, blockchain has a jargon problem that makes the technology sound downright radioactive.

The Curse of Blockchain’s Elevator Pitch

One of the biggest challenges for understanding blockchain and why it’s so much more than just cryptocurrency is that — as an application platform — blockchain lacks its own easily digestible elevator pitch. No oft-cited raison d'être. No catchy jingle. You could be a novice riding on the Burj Khalifa’s 140-story elevator with the most eloquent blockchain expert on the planet, and you would be no more enlightened at the end of the ride than you were at the beginning about blockchain’s potential as a non-financial business technology or application platform.

Cryptocurrency, on the other hand, is much easier to grok. A 5-floor ascent to the top of a New York City brownstone would suffice. The reason? Practically every human on the planet has a basic understanding of money. To be clear, there are huge differences between fiat currencies like the US dollar and cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. However, whereas a grade-school grasp of fiat currency offers a foundation for the unique value proposition of crypto, there is simply no corollary for blockchain technology. The learning curve is steep, and for good reason; blockchain was a technological breakthrough that cracked the code on several obscure distributed computing problems to which very few mortals can truly relate, let alone understand.

Blockchain is like rocket science, and one reason that people are smitten with rocket science is that it often comes in a nice package that delivers a novel commodity of unprecedented value. And, although we may not fully understand what’s inside the nifty bundle known as ChatGPT, marketers have cleverly gift-wrapped its proposition into two words that tell us everything we need to know and love about it: “artificial intelligence.”

But when the most admired evangelists were assembling their blockchain messages for mass consumption, they checked their semantic common sense at the door. Almost comically, one of blockchain’s most important qualities is now summarized in the one-word catchphrase “trustless,” which virtually guarantees to offend the sensibilities of the very people — lawmakers, regulators, policymakers, and the C-suite — who need to be convinced of the technology’s unique ability to do the opposite; inspire trust. You might as well tell all the swimmers who show up at the beach that there’s a family of great white sharks hanging around the shallows when, in reality, it's safe to swim.

Blockchain’s Recipe For Revitalizing Trust

The key to understanding how blockchain can infuse trust into just about any institutional process is to holistically consider the key sources of distrust and how to rise to the challenge of earning and keeping trust.

“Trust is built from within. So you start within. You identify those gaps, and then you repair those. So let's just say data integrity and protection,” says Deloitte’s Bondar, hinting at one of the biggest sources of distrust; data authenticity. In the course of engendering trust or assuaging compliance-sensitive stakeholders (regulators, lawyers, watchdogs, chief compliance officers, etc.), any organization can take transparency to the extreme. But, so long as a single party controls the underlying data’s production, storage, retrieval, and presentation — collectively, the recordkeeping practices — that information is at best too easily challenged and at worst, suspect due to a continued pattern of record tampering by organizations of all types. Under the current regime of transparency (and given the advance of technologies that are capable of very convincing alternate realities), the grand majority of the world’s data could not be proven true beyond a reasonable doubt.

Fortunately, in an American court of law, guilt must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt (instead of truth). But the same cannot be said of the court of public opinion where most judgments about the trust, guilt, or innocence of most institutions are made. For the grand majority of the world’s records, questions like “How authentic is the data or might it be bogus?”, “Who or what had access to data along its journey and how might it have changed?”, and “Is a presentation of some data an accurate reflection of that data’s most authentic version?” are largely unanswered today. To revitalize trust in the world’s institutions and their recordkeeping practices, these and other gaps must be closed and, according to Deloitte’s Bondar, the provenance and security of data along with a healthy dose of transparency is as good a place as any to begin.

“Take appropriate measures to safeguard the data. Make the technologies you're employing visible to the outside world. We're implementing these techniques, these capabilities, to safeguard your data, Mr. Consumer, Mrs. Consumer, that's part one” says Bondar. “Second, ensure that these capabilities are highly effective and that your employees, as well as the outside world, as having that right intent. Not a check-the-box exercise, but we're meaningfully engaging in this.”

To be clear, no technology — not even blockchain — is a silver bullet to a challenge as big as a global revolution in trust. Similar to the way that Benioff recognized that “customers work with us because they trust us,” and then ingrained trust as a priority in every Salesforce employee's brain, any initiative to revitalize trust in any data, organization, process, or setting depends first on a cultural shift and a reverence for the truth. And then there's the need for technological measures to automate that trust as best as possible. Across the technology landscape, there is no technology (whether it’s “out of the box” or customized) that is ready-made for that challenge the way blockchain is.

What Makes Blockchain So Special?

To appreciate the first of blockchain’s superpowers and its application to any process or data, lawmakers and business executives need only reflect on their respect for the role that independence plays in third-party audits. Specifically, this relates to the idea that the auditor is free (or at least significantly freer than an internal auditor) from any conflicts of interest that could interfere with a truthful and honest audit. In situations where organizations have revealed the outcomes of their own internal audits, those audits are often viewed by stakeholders with suspicion and skepticism. Despite their best intentions, internal auditors are not nearly as free from undue influence as third-party auditors whose reputations depend on their independence. The involvement of a third-party auditor engenders significantly more trust in the outcome of an audit than an internal audit ever can.

But, in this age of deep fakes, artificial intelligence, and other technologies that call the very provenance of the data being audited into question, audits — even third-party audits — involve one significant shortcoming that threatens their legitimacy: They most often start after the recordkeeping has already taken place. For a truly honest audit, the onus is therefore on the third-party auditor to not only audit the records but to reverse-engineer and audit the origins of those records. Even for the most skilled auditors, it’s a daunting task that in many cases can involve the obstruction of their work by insider efforts to cover up the truth.

In contrast to auditing where the significance of third-party independence most often comes into play well after the recordkeeping has already started, blockchain applies the same dispassionate, conflict-of-interest-free independence of randomly selected third parties to the genesis of those records. In other words, whereas many technology discussions involve the so-called "last mile" of some process (e.g., the last mile of telecommunications, the last mile of a supply chain,, etc.), blockchain’s infusion of trust into non-crypto applications can happen during the first mile (at the origin of institutional recordkeeping). Ergo, if auditing is what comes “after,” blockchain is what comes “before.”

How Blockchain Can Secure the First Mile of Any Record’s Journey

A significant part of blockchain’s potential to infuse trust into existing and new applications is therefore based on the disintermediation of any conflicts of interest from the most important part of any record’s life. Typically, the “before” part is when the record’s authenticity is determined for the rest of its existence; unfortunately, this part too often includes the opportunity for the books to be cooked or corrupted by malfeasance or incompetence. It’s the part that, until blockchain came along, made a record — of anything and everything — only as reliable as the least trustworthy mile of its journey: the first mile. Blockchain not only solves this problem for records in ways that no other technology can, but it also does this for the recordkeeping of the recordkeeping.

Blockchain’s inborn capability to recruit conflict-free third parties (known as “validators” in blockchain circles) into an institutional record-making role — thereby closing out one of the last remaining opportunities to deliberately or inadvertently corrupt the truth — is one of its key differentiators from antecedent technologies such as databases. Whereas databases will remain the foundation for housing the world’s records for the foreseeable future (as indicated by the aforementioned IDC report), blockchain is the complementary technology that adds trust to those records by introducing a third-party-driven conflict-free governance model that no database can offer.

For those keeping score, the terms “decentralized” and “trustless” — as horrible as they are at communicating the value of blockchain — were derived from this innate capability of blockchain to democratize recordkeeping governance. Decentralizing that governance means replacing the entities that are centrally in control of the data (and therefore are in an unchecked position to corrupt it according to their interests) with third parties who have no personal or business interest in the data itself and are only concerned with being compensated for their participation in the governance process.

“Trustless” is therefore a reference to the absence of any central entity or entities as trusted caretakers of the governance process. The most commonly discussed context for this so-called trustlessness involves the disintermediation of banks as trusted overseers of monetary transactions. But this crypto-related reference to financial recordkeeping is merely an example of blockchain’s power to outsource recordkeeping governance.

In the interest of earning and keeping trust, blockchain’s second-inborn superpower, which is not found in any other technology, dovetails the first. Once a record of something — anything — is made on a public blockchain, it is immutable. In other words, it is indelibly transcribed and forever publicly accessible (especially to auditors and regulators) to the extent that no party — especially a central party that, in its own interests, might try to corrupt or delete that record — can initiate such a unilateral action.

As an example, suppose X (formerly Twitter) decided to use blockchain to ingratiate its Tweet-publishing workflow with an added layer of trust. At the moment a Tweet is published, X’s Tweet-publishing workflow could also post a cryptographic hash of that Tweet to a public blockchain. Thanks to blockchain’s superpower of immutability, that post will forever document the existence of that original Tweet. No party — not the original author of the Tweet, not X, nor anyone else — would have the power to change the blockchain’s record of that Tweet in any way. Should the actual Tweet as it exists on X’s systems (not the record of it on the blockchain) subsequently be tampered with in any way (by X, by a hacker, etc.), it would be the equivalent of breaking the tamper-proof seal on a bottle of aspirin. While it does not automatically imply malfeasance, it would suggest that at some point since the genesis of the original Tweet, some aspect of the Tweet was changed in a way that could merit further attention.

Another example, particularly where both the record and recordkeeping have recently been contested, involves the provenance and therefore the truthfulness of birth records. In the case of Donald Trump, he previously challenged Barack Obama’s eligibility to be US President based on his birth record and therefore his status as a natural-born citizen. Then, in the current US Presidential election cycle, Trump has once again raised a similar challenge.

In June 2008, the BBC reported:

... the Obama campaign released a photocopy of his short-form ‘certificate of live birth’ showing that he was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, on August 4th, 1961... [but critics] questioned the authenticity of the document and demanded the ‘long-form’ certificate from the Democrat's birth hospital.

In January 2024, Trump also questioned the Presidential eligibility of his closest Republican rival, South Carolina Governor, Nikki Haley.

In both cases, it does not matter which side of the challenge one favors. What matters is fast, public access to the unimpeachable truth. Had public blockchains been available at the moment that both Obama and Haley were born, an accurate record of their births could have been permanently enshrined on a blockchain so that anyone could investigate and confirm the provenance and authenticity of those records. If, decades after their birth, a presidential candidate shared a copy of their birth certificate, the authenticity of that document would be verifiable by anybody with little more than the click of a mouse. Just the existence and common knowledge of such tamper-proof records — any records in any context, not just birth records in an election contest — would act as a deterrent to certain controversies and the headlines that result.

The birth certificate analogy is also apropos of news from Sony that is coming out of the 2024 edition of the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas. According to TechCrunch, Sony “has announced the development of an in-camera digital signature technology, which effectively creates a ‘birth certificate’ for images captured with their devices, thereby verifying the origin of the content.”

At the 2024 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Sony announced the Alpha 9 III, a full-sensor camera that uses the C2PA cryptographic metadata standard to digitally sign the pictures it takes, which — for the remainder of a photo’s life — enables subsequent manipulations of that photo to be detected easily.

During the announcement, Sony Electronics president and COO Neal Manowitz discussed how the consumer electronics giant is “collaborating with the Associated Press and other industry leaders to create a digital birth certificate for images shot on our cameras. This will validate the origin of their content and help safeguard facts and combat misinformation.”

DPreview elaborated on the authentication capabilities of the Sony A9 III as follows:

Sony says it plans to add C2PA authentication to the A9 III [camera]. This is a cryptographic metadata standard developed by a range of software makers, camera makers and large media organizations that will provide a secure record of the file's provenance and edit history, allowing media organizations to know that the images they are receiving can be traced back to a specific camera and haven't been inappropriately manipulated.

In a similar collaboration involving a C2PA-compliant camera from Canon, the Starling Lab for Data Integrity (associated with Stanford University’s Center for Blockchain Research) is working with Reuters to, among other things, track the provenance of digital images (see Reuters Photojournalism Authentication Pilot) that are used in photojournalism to help prevent misinformation.

In a 2023 interview with Blockchain Journal, Starling Lab COO Adam Rose discussed how, with the help of blockchain, “authenticity data could travel along with photographs that [Reuters] produced through a professional Newsroom workflow.” According to Rose:

[Reuters has a] very robust newsroom where they've got a lot to do in terms of not just taking a photo, but you think about the whole life cycle of that [record] from the moment of capture on a camera when the light hits the sensor through different steps of normal photo editing. You think about permissible edits like color corrections and crops and then ultimately to distribution and then how do audiences find that information and then find ways to verify that it is the original photo as it purports to be?

In the spirit of the first mile of a record’s life — the period when the underlying data is most vulnerable to fraudulent or negligent influence — Rose’s words “from the moment of capture” have broader implications for how trust in all recordkeeping can be improved through (1) the foreclosure on human interference during the earliest moments in a record’s life and (2) the involvement of blockchain. On its website, Reuters discusses usage of blockchain technology to protect photojournalistic integrity: “The authenticated picture's pixels, GPS and other metadata, are sent to the Reuters system directly from the camera and registered onto a public blockchain.” In other words, other than pressing the camera’s shutter button to snap the photo, there is little to no opportunity for the introduction of human interference before the photo’s most authentic details are transparently and permanently committed to public infrastructure.

The relevance of Starling Lab’s work on blockchain-based verification of image authenticity and provenance stretches beyond journalism into other use cases. One such example is crime scene photos where, today, the veracity of photographic evidence is easily challenged given the widespread availability of sophisticated image and video manipulation tools that grade schoolers now use every day.

The Starling Lab/Reuters workflow serves as a model for how trust in all of the world’s records can be revitalized. From the Tweet to the birth certificates to the Sony and Starling Lab examples, there are certainly thousands if not millions of other similar recordkeeping use cases. The common theme with these use cases is the increasing degree to which humans — and therefore the opportunity to introduce malfeasance or incompetence — are eliminated from the first mile of recordkeeping, while at the same time needing blockchain and its community of conflict-free third parties to enshrine and preserve the integrity of there records for whatever future challenges may arise.

Keeping Check on Artificial Intelligence (or Any Automated Process)

As the world’s digital infrastructure grows to absorb all of its data like a sponge (per the IDC study) and Moore’s law continues to drive system performance to unprecedented levels, the automation of certain business and government outcomes has left virtually no opportunity for humans to intervene in those results before they happen. Programmed stocked trading is perhaps the best-known example of this phenomenon.

Throughout recent stock market history, there have been multiple instances where computer-based algorithmic trading has triggered isolated as well as market-wide meltdowns. Under the headline "Too Fast to Fail: How High-Speed Trading Fuels Wall Street Disasters", Mother Jones describes how one firm nearly went out of business in the blink of an eye:

In the Jersey City offices of a midsize financial firm called Knight Capital, panic was setting in. A program that was supposed to have been deactivated had instead gone rogue, blasting out trade orders that were costing Knight nearly $10 million per minute. And no one knew how to shut it down. At this rate, the firm would be insolvent within an hour. Knight’s horrified employees spent an agonizing 45 minutes digging through eight sets of trading and routing software before they found the runaway code and neutralized it.

The story continues with a sobering conclusion:

Despite efforts at reform, today’s markets are wilder, less transparent, and, most importantly, faster than ever before. Stock exchanges can now execute trades in less than half a millionth of a second—more than a million times faster than the human mind can make a decision.

Concern over the lightning speed of algorithmic trading and “programmed” meltdowns of this nature have been the impetus for the implementation of so-called circuit breakers. According to Investopedia, “In trading, circuit breakers are emergency measures established by stock markets that shut down trading activity temporarily or for the rest of the trading day when market prices drop significantly.” In other words, the algorithmic trading forensics have yet to evolve beyond the point at which the only answer is the equivalent of pulling the system’s plug out of the wall.

When Mother Jones cited the lack of transparency, it was no doubt referring, at least in part, to the absence of those forensics.

Today, in 2024, the scalability and rapid decision-making of artificial intelligence presents society with a nearly identical problem across a wide range of domains (not just the trading of stocks) and is equally if not more opaque than algorithmic trading ever was. It’s not a question of if artificial intelligence will go off the rails similarly to algorithmic trading. It already has.

For example, in What Do We Do About the Biases in AI?, Harvard Business Review noted:

[AI can] make the problem worse by baking in and deploying biases at scale in sensitive application areas. For example, as the investigative news site ProPublica has found, a criminal justice algorithm used in Broward County, Florida, mislabeled African-American defendants as ‘high risk’ at nearly twice the rate it mislabeled white defendants. Other research has found that training natural language processing models on news articles can lead them to exhibit gender stereotypes.

Whether it’s stock trades, law enforcement, or any algorithmically driven process, blockchain represents an opportunity to programmatically make and preserve a public record of not just every fork in the road that an algorithm encountered, but also what that algorithm did at that fork. Such forensic evidence could not only lead to less catastrophic algorithm results, but the real-time nature of the forensic production — as an algorithm is doing what it is programmed to do — can lead to new and improved outcomes.

However, blockchain applications concerning artificial intelligence go beyond the interception and truthful logging of business logic outcomes. As the Harvard Business Review article notes, “AI systems learn to make decisions based on training data.”

According to Casper Labs CEO Mrinal Manohar, those records, like most records, could be manipulated to change the decisions and outcomes that happen as a result of AI. In an interview with Blockchain Journal, Manohar explains:

The volume of [AI] interactions is just going to be so large that having this automated tamper-proof system is incredibly important. Because when you're dealing with incredibly large volumes of either interactions, sessions, etc., auditing them becomes a huge pain if you don't know that the audit path has not been tampered with. And that's why the tamper-proofing [nature of blockchain] is incredibly important.

The most visceral example of tamper-proofing could be a life-or-death matter. During an interview with NPR, Thom Shanker, a journalist and co-author of the book Age of Danger, described one of the most important means by which a warring party gains a battlefield advantage over its opponent:

There's a military axiom that says speed kills. If you see first, if you assess first, if you decide first, if you act first, you have an incredible advantage.... As weapons get faster, like hypersonic [missiles], when they can attack at network speed, like cyberattacks, humans simply cannot be involved in that. So you have to program, you have to put your best human intellectual power into these machines and hope that they respond accordingly.

The role of AI in this scenario is unmistakable. But Shanker then asks about the potential impact of human error:

But as we know in the real world, humans make mistakes. Hospitals get blown up. Innocents get killed. How do we prevent that human error from going into a program that allows a machine to defend us at network speed, far faster than a human can?

But the cloak and dagger questions Shanker doesn’t broach are equally concerning; What if an adversary has tampered with the underlying data on which the artificial intelligence depends to make its battlefield decisions? What if that machine-learning data model is re-used across other military applications? To what extent can the developers of those AI applications rest assured that they’re working with the right data?

Desperately Seeking: Regulatory Clarity for Blockchain (Versus Crypto)

So, given the widespread erosion of trust in today’s institutions and with all of this nearly limitless potential of blockchain to cost-effectively add trust as though it were infrastructure for existing and new applications that cover a wide range of business and societal domains, one question remains; why are US enterprises hesitating to embrace and innovate with it?

According to several experts interviewed by Blockchain Journal, the answer lies in how blockchain and crypto are often conflated to the point that they’re considered to be synonymous with one another.

During the December 2023 edition of the Boston Institutional Assets Forum, Oasis Pro CEO Pat LaVecchia described to Blockchain Journal how business executives mistakenly “see all this bad news coming out about crypto and they view blockchain and crypto as the same.” As a result, LaVecchia spends a lot of time explaining to the C-suite that yes, “crypto needs blockchain to succeed, but blockchain is its own technology.” For businesses that are looking to avoid disruption at the hands of blockchain-savvy technologists, agile executives and IT professionals must discover and respond to blockchain’s potential (entirely separate from that of crypto) to drive business advantages in ways that antecedent technologies cannot. At the 2023 DC Blockchain Summit, Wendy Henry, one of the global leaders of Deloitte’s digital asset practice told Blockchain Journal that businesses “can’t just sit on the sidelines and wait for everyone to figure this out. You’ll be left behind.”

Although many American enterprises are feeling the urge to get started with blockchain, they see too much risk in the current regulatory landscape. When it comes to blockchain adoption, the hesitation of US enterprises is often misinterpreted as a result of their fear of regulation. But, unlike in other business domains where enterprises might lobby for more freedom to operate through deregulation or no regulation, most enterprises just want regulatory clarity when it comes to blockchain.

During a fireside chat at the 2023 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Circle’s COO Elisabeth Carpenter described to Rob Massey (another one of the global leaders of Deloitte’s Digital Assets Practice) the idea of a constantly “shifting regulatory perimeter” that businesses must stay vigilant about if they are going to move forward, even though no American blockchain or cryptocurrency laws have been passed. Following that chat, Massey told Blockchain Journal, “Not only are the rules shifting. Sometimes the rules don't exist yet, and so we're waiting for clarity.”

So long as that clarity doesn’t exist, many enterprises are justifiably reluctant about going too far down one path only to wake up one morning to a bunch of law enforcement officials in blue windbreakers at their front door. Therefore, for businesses, it’s a Catch-22. If they hold off on blockchain innovation, they may get left behind. If they move forward, they risk possible enforcement activity down the line.

For lawmakers and regulators who are wrestling to protect their constituents from the current radioactivity of crypto while at the same time offering the sort of legal certainty that promotes blockchain innovation, the imperative is to disentangle blockchain from crypto so the latter doesn’t discourage technology leadership with the former. Blockchain Journal’s ongoing research into global enterprise adoption reveals a pattern of American companies setting up blockchain innovation centers in more strategic thinking, blockchain-friendly jurisdictions such as Germany, Switzerland, Singapore and the UK. Referring to investments in blockchain innovation, Aon managing director James Knox shared the following with Blockchain Journal:

We are seeing jurisdictions around the world outside the US offer investors and finance institutions more regulatory clarity in the digital asset space. So it's not surprising where that money is going to go. Investments are going to go where there's more regulatory clarity.